by Avi Davis and Michael Lotus

Every second Monday in October in the United States, the banks close, the post office shuts down, federal services are unavailable and many local public services cease to operate. It is the day in the calendar designated by our government to celebrate Christopher Columbus’ first landing in the New World.

Many American citizens believe that the public holiday marks the discovery of the land mass which would come to be known, three hundred years later, as the United States of America.

This is not true. Christopher Columbus, in none of the four Atlantic voyages of discovery he undertook from the Kingdom of Spain, ever set foot on the continent of North America. The date October 12, 1492 only marks the day upon which he discovered an island off the coast of Cuba in the Caribbean – which some consider present day San Salvador Island and others consider Samana Cay.

What, in fact, we truly celebrate on the second Monday of October each year is not the discovery of the American continent(s) but rather the joining of the Old and New Worlds – for this essentially marks the modern beginnings of what was to become known as the Western world.

The sudden opening to Europeans of the Western Hemisphere, and the contemporaneous discovery of sea routes to Asia, is one of many links in the chain of causation that led to the modern world. These sea voyages were essential early steps on the near-miraculous steps by which agrarian mankind escaped from the Malthusian trap of pre-industrial civilization which offered a finite consumption of resources and no exit. The once-in-history escape from this fate is therefore referred to by Ernest Gellner and Alan Macfarlane as’ The Exit,’ which originated in England and was then adapted to local conditions and replicated around the world.

Another way to describe this unique and world-transforming change is, in Jim Bennett’s words,” the triumph of production over predation.” In a post-Exit world, exploitation of other humans beings, by slavery and other more subtle means, no longer became the primary path to wealth and power.

Would the Exit have occurred without the linking of the Old World with the New?

We can never be sure. Similarly, we can’t say for certain that the particular combination of history, technology, and geography that led the British Isles to become the driving force for the European Exit was either inevitable or would never be duplicated in another place or time.

What is clear, however , is that the chain of events set in motion by Columbus, Cabot, Verrazzano, Cartier and Jolliet and the other European explorers, resulted in a shift of populations from one hemisphere to another – populations which would inevitably be linked by common heritage, law and language and creating a network of trade and cultural exchange which has survived to this day.

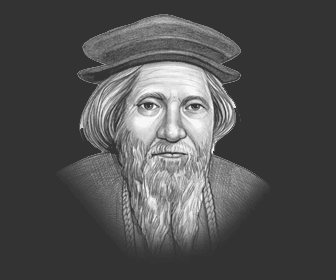

A further detail worth mentioning on Columbus Day is the observation that we in the Anglosphere may be celebrating the wrong Italian. That is because there were really four European discoveries and settlements in the Western Hemisphere – a Spanish one -in the Caribbean and Mexico ( as well as points further south); a Portuguese one in Brazil; a French one in the valleys of the St. Lawrence and Mississippi Rivers and an English one along the eastern coast of North America. In this regard, we should not forget that the explorations of John Cabot (Giovanni Caboto), on assignment from the King of England in 1497 were the first recorded English commissioned incursions into North America.

So, while giving Columbus his due for uniting the Old and New Worlds, let us also celebrate the achievements of the Venetian sailor John Cabot, commissioned by Henry VII of England, whose discoveries led to the planting of the Anglosphere in the New World — which, in turn, led in turn to America 1.0, America 2.0 and then America 3.0, which is now struggling to be born.

Avi Davis is the president of the American Freedom Alliance. Michael Lotus is a fellow of the American Freedom Alliance and a founder and senior researcher of the American 3.0 Institute.

Posted by avidavis

Posted by avidavis

America in Retreat: the New Isolationism and the Coming Global Disorder

America in Retreat: the New Isolationism and the Coming Global Disorder