by Avi Davis

Now that Greece has demanded additional reparations from Germany for that country’s WWII crimes on Greek territory, many other countries might well fall in line with their tin cups extended. Soon enough Russia will be demanding reparations from France for Napoleon I’s invasion of 1812 and India might make the same demands of Uzbekistan for Tamerlane’s brutal incursion of the 14th Century. And lets not forget the Anglo-Saxons who might want some compensation for the 300 years of Norman occupation of England from 1066 onward.

Don’t get me wrong. The Germans committed heinous acts in Greece 1941-44, occupying that country for four very long years during the Second World War, deporting hundreds of thousands and exacting a terrible price from the Greeks.

But the Germans already paid and the Greeks accepted extensive reparations in the 1950s and 60s. That includes about $54 million to Greece and its citizens, an amount that would be roughly $450 million today when adjusted for inflation. No Greek public figure has made a claim for extra compensation from the Germans since that time and extra reparations have certainly not been a focal point of Greek/German relations in any sense in the intervening years. But now some Greek politicians claim Germany owes the country more than €160 billion ($181 billion) in reparations.

Why now then? Because the Greeks need leverage to use against the Germans in attempting to restructure ( another word for forgive) their debt so that that they can climb out of the crater their new leftist government is presently digging them and from which there will be no way out except via a rope thrown down by the Germans.

To me this sort of reads like the kid who skips school for the entire semester and then blames his teacher and the school’s bias for his failure in the year’s final exams.

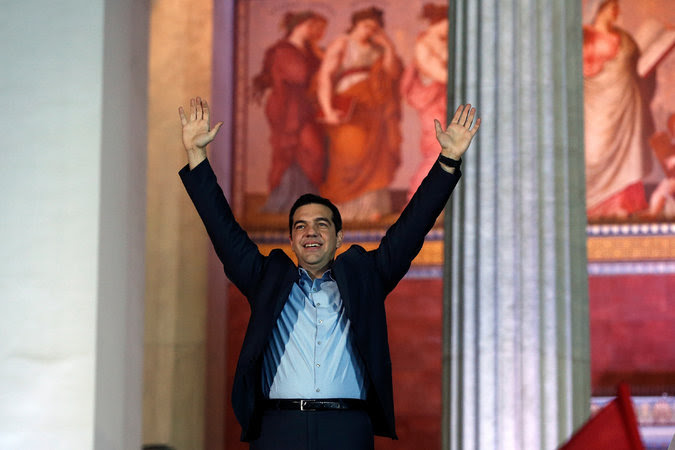

It should not be lost on anyone that three years ago the Germans rescued the Greek economy from certain collapse when Government debt – already at 180% to GDP – was spiraling so far out of control that it looked like if the drain on Europe was not plugged it would empty the entire European economic experiment into the Aegean. The Germans came to the rescue but demanded substantial reforms – and thus the imposed austerity measures about which so many Greeks are today complaining and which ushered in the leftist government of the inexperienced Alex Tsirpas.

But so far the Germans are having none of the Greek petulance and seem unlikely to yield on their demand that in order to renew loans due on February 28th the Greek government must absolutely commit to the same austerity measures which essentially brought down the last government.

No one , however, should mistake this for a stalemate. Tsirpas’ government may think that it has the upper hand because skittish EU bureaucrats in Brussels, looking down the long barrel of the rapid devaluation of the Euro, will not allow Greece to simply walk away from the currency – which would be the inevitable result of a massive default on government debt.

However the German central banks – which are the real power behind the Euro – have so far expressed remarkable determination and show no willingness to renegotiate Greek debt with Tsirpas’ envoys.

Which brings us to the issue of the reparations. They are a clearly transparent and cynical means of building resentment against the Germans, adding fuel to a fire which had already caught ablaze among the Greek public and has enticed them into this present sleep walk over a very steep fiscal cliff.

And here’s what that fiscal cliff looks like:

Greece’s bailout from the eurozone runs out on Feb. 28. At that moment, without an extension, it will lose its last €1.8 billion disbursement from the currency union’s bailout fund, €1.9 billion in profits from Greek government bonds held by the European Central Bank and around €11 billion still sitting in Greece’s bank bailout fund. The fate of a €3.5 billion transfer from the International Monetary Fund is less obvious, since the IMF’s program for Greece runs until the end of 2016. What is clear is that Athens won’t get any money from the fund without an agreed aid deal with the eurozone.

Greek government officials have said that they could run out of money in early March, especially if tax revenues deteriorate further. At that point, the government won’t be able pay things like pensions and public-sector salaries. Crucially, for the eurozone and the IMF, it also won’t be able to repay its creditors, including the fund and the ECB. Between March and August, Greece has to repay €4.7 billion in old IMF loans and €6.6 billion in bonds held by the ECB and national central banks. Those numbers don’t include interest payments to private creditors, the fund and the eurozone along with a few smaller redemptions. They also don’t include €13.4 billion in short term debt, so-called Treasury bills, that Greece needs to roll over by the end of August.

So in order top restructure that debt, the Greeks desperately need time – or else the trains, which rarely run on time anyway, will really stop running altogether.

So what happens now?

Almost certain default. Cut off from rescue funding, Greek banks would suffer dramatic cash outflows as depositors worried about Greece being forced out of the single currency region. Currently, the European Central Bank’s emergency liquidity assistance program, operated by the national central bank, ensures that Greek banks have enough cash to cover depositor outflows. Because depositors know this, there hasn’t been a stampede of funds out of the banks.

Yet.

But without the ECB, the flight of funds would cascade, threatening a Greek banking collapse. Greece would be forced to put up capital controls, limiting withdrawal of funds, and force the banks’ creditors to take losses.

Ernest Hemingway once wrote there are two stages to going bankrupt: “Gradually, then suddenly.” He could just as easily have been referring to the process of being ejected from the eurozone.

Greece’s sudden banruptcy will hurt everyone – even us here in the United States. But it might be preferable to have a temporary electric shock than a long painful death from a million minor cuts.

Avi Davis is the president of the American Freedom Alliance and the editor of the Intermediate Zone

Posted by avidavis

Posted by avidavis

…

…